- Very Rare Medieval Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures Verses

- Very Rare Medieval Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures King James Version

Explore thousands of old and rare books, including illuminated manuscripts, fine press editions, illustrated books, incunabula, limited editions and miniature books. Whether you're a budding rare book collector or a bibliophile with an enviable collection, discover an amazing selection of rare and collectible books from booksellers around the.

- Very Rare Medieval Apocrypha III Very Rare Medieval Apocrypha IV BARLAAM AND IOASAPH (complete MS) OGIAS THE GIANT Manuscript Photos PDF FILES. The Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments. The secular tribunals should not be competent to resolve purely religious matters, nor to sentence whosoever does not believe what the majority believes.

- Historiography of early Christianity is the study of historical writings about early Christianity, which is the period before the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Historians have used a variety of sources and methods in exploring and describing Christianity during this time.

- The New Testament apocrypha (singular apocryphon) are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings have been cited as scripture by early Christians, but since the fifth century a widespread consensus has emerged limiting the New Testament to the 27 books of.

- Old Testament apocrypha may date from the 2nd century BCE to the early Middle Ages, New Testament apocrypha continued to be produced well into the medieval period, and some overlap exists between the two. Some Old Testament apocrypha are extant in Hebrew or Aramaic, but frequently the original is fragmentary or only presumed on philological.

hidden

(concealed, hidden).

- Old Testament Apocrypha ._The collection of books to which this term is popularly applied includes the following (the order given is that in which they stand in the English version); I. 1 Esdras; II. 2 Esdras; III. Tobit; IV. Judith; V. The rest of the chapters of the book of Esther, which are found neither in the Hebrew nor in the Chaldee; VI. The Wisdom of Solomon; VII. The Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach, or Ecclesiasticus; VII. Baruch; IX. The Song of the Three Holy Children, X. The History of Susanna; XI. The History of the destruction of Bel and the Dragon; XII. The Prayer of Manasses king of Judah; XIII. 1 Maccabee; XIV. 2 Maccabees. The primary meaning of apocrypha , 'hidden, secret,' seems, toward the close of the second century to have been associated with the signification 'spurious,' and ultimately to have settled down into the latter. The separate books of this collection are treated of in distinct articles. Their relation to the canonical books of the Old Testament is discussed under CANON OF SCRIPTURE, THE.

- New Testament Apocrypha -- (A collection of legendary and spurious Gospels, Acts of the Apostles, and Epistles. They are go entirely inferior to the genuine books, so full of nonsensical and unworthy stories of Christ and the apostles, that they have never been regarded as divine, or bound up in our Bibles. It is said that Mohammed obtained his ideas of Christ entirely from these spurious gospels.--ED.)

Signifies properly hidden, concealed; and as applied to books, it means those which assume a claim to a sacred character, but are really uninspired, and have not been publicly admitted into the canon. These are of two classes: namely,

1. Those which were in existence in the time of Christ, but were not admitted by the Jews into the canon of the Old Testament, because they had no Hebrew original and were regarded as not divinely inspired. The most important of these are collected in the Apocrypha often bound up with the English Bible; but in the Septuagint and Vulgate they stand as canonical.

These apocryphal writings are ten in number: namely, Baruch, Ecclesiasticus, Wisdom of Solomon, Tobit, Judith, two books of the Maccabees, Song of the Three Children, Susannah, and Bell and the Dragon. Their style proves that they were a part of the Jewish- Greek literature of Alexandria, within three hundred years before Christ; and as the Septuagint Greek version of the Hebrew Bible came from the same quarter, it was often accompanied by these uninspired Greek writings, and they thus gained a general circulation. Josephus and Philo, of the first century, exclude them from the canon. The Talmud contains no trace of them; and from the various lists of the Old Testament Scriptures in the early centuries, it is clear that then as now they formed no part of the Hebrew canon. None of them are quoted or endorsed by Christ or the apostles; they were not acknowledged by the Christian fathers; and their own contents condemn them, abounding with errors and absurdities. Some of them, however, are of value for the historical information they furnish, for their moral and prudential maxims, and for the illustrations they afford of ancient life.

2. Those which were written after the time of Christ, but were not admitted by the churches into the canon of the New Testament, as not being divinely inspired. These are mostly of a legendary character. They have all been collected by Fabricius in his Codex Apoc. New Testament.

(1.) They are not once quoted by the New Testament writers, who frequently quote from the LXX. Our Lord and his apostles confirmed by their authority the ordinary Jewish canon, which was the same in all respects as we now have it.

(2.) These books were written not in Hebrew but in Greek, and during the 'period of silence,' from the time of Malachi, after which oracles and direct revelations from God ceased till the Christian era.

(3.) The contents of the books themselves show that they were no part of Scripture. The Old Testament Apocrypha consists of fourteen books, the chief of which are the Books of the Maccabees (q.v.), the Books of Esdras, the Book of Wisdom, the Book of Baruch, the Book of Esther, Ecclesiasticus, Tobit, Judith, etc.

The New Testament Apocrypha consists of a very extensive literature, which bears distinct evidences of its non-apostolic origin, and is utterly unworthy of regard.

1. (n. pl.) Something, as a writing, that is of doubtful authorship or authority; -- formerly used also adjectively.2. (n. pl.) Specif.: Certain writings which are received by some Christians as an authentic part of the Holy Scriptures, but are rejected by others.

ad'-am, ('adham; Septuagint Adam).

1. Usage and Etymology:

The Hebrew word occurs some 560 times in the Old Testament with the meaning 'man,' 'mankind.' Outside Genesis 1-5 the only case where it is unquestionably a proper name is 1 Chronicles 1:1. Ambiguous are Deuteronomy 32:8, the King James Version 'sons of Adam,' the Revised Version (British and American) 'children of men'; Job 31:33 the King James Version 'as' the Revised Version (British and American) 'like Adam,' but margin 'after the manner of men'; Hosea 6:7 the King James Version 'like men,' the Revised Version (British and American) 'like Adam,' and vice versa in the margin. In Genesis 1 the word occurs only twice, 1:26, 27. In Genesis 2-4 it is found 26 times, and in 5:1, 3, 4, 5. In the last four cases and in 4:25 it is obviously intended as a proper name; but the versions show considerable uncertainty as to the rendering in the other cases. Most modern interpreters would restore a vowel point to the Hebrew text in 2:20; 3:17, 21, thus introducing the definite article, and read uniformly 'the man' up to 4:25, where the absence of the article may be taken as an indication that 'the man' of the previous narrative is to be identified with 'Adam,' the head of the genealogy found in 5:1. Several conjectures have been put forth as to the root-meaning of the Hebrew word:

(1) creature;

(2) ruddy one;

(3) earthborn. Less probable are

(4) pleasant-to sight-and

(5) social gregarious.

2. Adam in the Narrative of Genesis:

Many argue from the context that the language of Genesis 1:26, 27 is general, that it is the creation of the human species, not of any particular individual or individuals, that is in the described. But

(1) the context does not even descend to a species, but arranges created things according to the most general possible classification: light and darkness; firmament and waters; land and seas; plants; sun, moon, stars; swimming and flying creatures; land animals. No possible parallel to this classification remains in the case of mankind.

(2) In the narrative of Genesis 1 the recurrence of identical expressions is almost rigidly uniform, but in the case of man the unique statement occurs (verse 27), 'Male and female created he them.' Although Dillmann is here in the minority among interpreters, it would be difficult to show that he is wrong in interpreting this as referring to one male and one female, the first pair. In this case we have a point of contact and of agreement with the narrative of chapter 2.

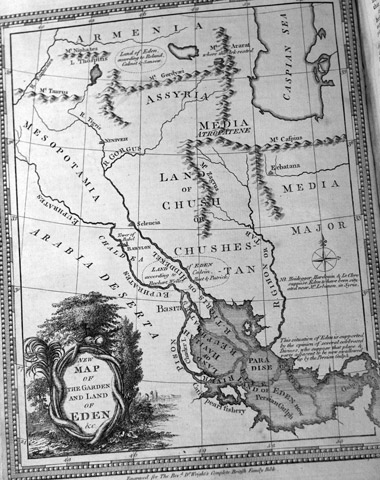

Man, created in God's image, is given dominion over every animal, is allowed every herb and fruit tree for his sustenance, and is bidden multiply and fill the earth. In Genesis 2:4-5:5 the first man is made of the dust, becomes a living creature by the breath of God, is placed in the garden of Eden to till it, gives names to the animals, receives as his counterpart and helper a woman formed from part of his own body, and at the woman's behest eats of the forbidden fruit of 'the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.' With her he is then driven from the garden, under the curse of brief life and heavy labor, since should he eat-or continue to eat?-of the fruit of the 'tree of life,' not previously forbidden, he might go on living forever. He becomes the father of Cain and of Abel, and of Seth at a time after the murder of Abel. According to 5:3, 5 Adam is aged 130 years at the birth of Seth and lives to the age of 930 years.

3. Teachings of the Narrative:

That man was meant by the Creator to be in a peculiar sense His own 'image'; that he is the divinely appointed ruler over all his fellow-creatures on earth; and that he enjoys, together with them, God's blessing upon a creature fit to serve the ends for which it was created-these things lie upon the surface of Genesis 1:26-31. In like manner 2-4 tell us that the gift of a blessed immortality was within man's reach; that his Creator ordained that his moral development should come through an inward trial, not as a mere gift; and that the presence of suffering in the world is due to sin, the presence of sin to the machinations of a subtle tempter. The development of the doctrine of the fall belongs to the New Testament. See ADAM IN THE NEW TESTAMENT; FALL, THE.

4. Adam in Apocrypha:

Allusions to the narrative of the creation and the fall of man, covering most points of the narrative of Genesis 1-4, are found in 2 Esdras 3:4-7, 10, 21, 26; 4:30; 6:54-56; 7:11, 46-48; Tobit 8:6, The Wisdom of Solomon 2:23; 9:2; 10:1, Ecclesiasticus 15:14; 17:1-4; 25:24:00; 40:01:00; 49:16:00. In both 2 Esdras and The Wisdom of Solomon we read that death came upon all men through Adam's sin, while 2 Esdras 4:30 declares that 'a grain of evil seed was sown in the heart of Adam from the beginning.' Aside from this doctrinal development the Apocrypha offers no additions to the Old Testament narrative.

F. K. Farr

APOCRYPHA

a-pok'-ri-fa:

I. DEFINITION

II. THE NAME APOCRYPHA

1. Original Meanings

(1) Classical

(2) Hellenistic

(3) In the New Testament

(4) Patristic

2. 'Esoteric' in Greek Philosophy, etc.

III. USAGE AS TO APOCRYPHA

1. Early Christian Usage

'Apocalyptic' Literature

2. The Eastern Church

(1) 'Esoteric' Literature (Clement of Alexandria, etc.)

(2) Change to 'Religious' Books (Origen, etc.)

(3) 'Spurious' Books (Athanasius, Nicephorus, etc.)

(4) 'List of Sixty'

3. The Western Church

(1) The Decretum Gelasii

(2) 'Non-Canonical' Books

4. The Reformers

Separation from Canonical Books

5. Heb Words for 'Apocrypha'

(1) Do Such Exist?

(2) Views of Zahn, Schurer, Porter, etc. (ganaz, genuzim)

(3) Reasons for Rejection

6. Summary

IV. CONTENTS OF THE APOCRYPHA

1. List of Books

2. Classification of Books

V. ORIGINAL LANGUAGES OF THE APOCRYPHA

VI. DATE OF THE APOCRYPHAL WRITINGS

LITERATURE

I. Definition.

The word Apocrypha, as usually understood, denotes the collection of religious writings which the Septuagint and Vulgate (with trivial differences) contain in addition to the writings constituting the Jewish and Protestant canon. This is not the original or the correct sense of the word, as will be shown, but it is that which it bears almost exclusively in modern speech. In critical works of the present day it is customary to speak of the collection of writings now in view as 'the Old Testament Apocrypha,' because many of the books at least were written in Hebrew, the language of the Old Testament, and because all of them are much more closely allied to the Old Testament than to the New Testament. But there is a 'New' as well as an 'Old' Testament Apocrypha consisting of gospels, epistles, etc. Moreover the adjective 'Apocryphal' is also often applied in modern times to what are now generally called 'Pseudepigraphical writings,' so designated because ascribed in the titles to authors who did not and could not have written them (eg. Enoch, Abraham, Moses, etc.). The persons thus connected with these books are among the most distinguished in the traditions and history of Israel, and there can be no doubt that the object for which such names have been thus used is to add weight and authority to these writings.

The late Professor E. Kautzsch of Halle edited a German translation of the Old and New Testament Apocrypha, and of the Pseudepigraphical writings, with excellent introductions and valuable notes by the best German scholars. Dr. Edgar Hennecke has edited a similar work on the New Testament Apocrypha. Nothing in the English language can be compared with the works edited by Kautzsch and Hennecke in either scholarship or usefulness. (A similar English work to that edited by Kautzsch is now passing through the (Oxford) press, Dr. R. H. Charles being the editor, the writer of this article being one of the contributors.)

II. The Name Apocrypha.

The investigation which follows will show that when the word 'Apocryphal' was first used in ecclesiastical writings it bore a sense virtually identical with 'esoteric': so that 'apocryphal writings' were such as appealed to an inner circle and could not be understood by outsiders. The present connotation of the term did not get fixed until the Protestant Reformation had set in, limiting the Biblical canon to its present dimensions among Protestant churches.

1. Original Meanings:

(1) Classical.

The Greek adjective apokruphos, denotes strictly 'hidden,' 'concealed,' of a material object (Eurip. Here. Fur. 1070). Then it came to signify what is obscure, recondite, hard to understand (Xen. Mem. 3.5, 14). But it never has in classical Greek any other sense.

(2) Hellenistic.

In Hellenistic Greek as represented by the Septuagint and the New Testament there is no essential departure from classical usage. In the Septuagint (or rather Theodotion's version) of Daniel 11:43 it stands for 'hidden' as applied to gold and silver stores. But the word has also in the same text the meaning 'what is hidden away from human knowledge and understanding.' So Daniel 2:20 (Theod.) where the apokrupha or hidden things are the meanings of Nebuchadnezzar's dream revealed to Daniel though 'hidden' from the wise men of Babylon. The word has the same sense in Sirach 14:21; 39:3, 7; 42:19:00; 48:25:00; 43:32:00.

(3) In the New Testament.

In the New Testament the word occurs but thrice, namely, Mark 4:22 and the parallel Luke 8:17Colossians 2:3. In the last passage Bishop Lightfoot thought we have in the word apokruphoi (treasures of Christ hidden) an allusion to the vaunted esoteric knowledge of the false teachers, as if Paul meant to say that it is in Christ alone we have true wisdom and knowledge and not in the secret books of these teachers. Assuming this, we have in this verse the first example of apokruphos in the sense 'esoteric.' But the evidence is against so early a use of the term in this-soon to be its prevailing-sense. Nor does exegesis demand such a meaning here, for no writings of any kind seem intended.

(4) Patristic.

In patristic writings of an early period the adjective apokruphos came to be applied to Jewish and Christian writings containing secret knowledge about the future, etc., intelligible only to the small number of disciples who read them and for whom they were believed to be specially provided. To this class of writings belong in particular those designated Apocalyptic (see APOCALYPTIC LITERATURE), and it will be seen as thus employed that apokruphos has virtually the meaning of the Greek esoterikos.

2. 'Esoteric' in Greek Philosophy, etc.:

A brief statement as to the doctrine in early Greek philosophy will be found helpful at this point. From quite early times the philosophers of ancient Greece distinguished between the doctrines and rites which could be taught to all their pupils, and those which could profitably be communicated only to a select circle called the initiated. The two classes of doctrines and rites-they were mainly the latter-were designated respectively 'exoteric' and 'esoteric.' Lucian (died 312; see Vit. Auct. 26) followed by many others referred the distinction to Aristotle, but as modern scholars agree, wrongly, for the exoterikoi logoi, of that philosopher denote popular treatises. The Pythagoreans recognized and observed these two kinds of doctrines and duties and there is good reason for believing that they created a corresponding double literature though unfortunately no explicit examples of such literature have come down to us.

In the Greek mysteries (Orphic, Dionysiac, Eleusinian, etc.) two classes of hearers and readers are implied all through, though it is a pity that more of the literature bearing on the question has not been preserved. Among the Buddhists the Samga forms a close society open originally to monks or bhikhus admitted only after a most rigid examination; but in later years nuns (bhikshunis) also have been allowed admission, though in their case too after careful testing. The Vinaya Pitaka or 'Basket of Discipline' contains the rules for entrance and the regulations to be observed after entrance. But this and kindred literature was and is still held to be caviare to outsiders. See translation in the Sacred Books of the East, XI (Rhys Davids and Oldenberg).

III. Usage as to Apocrypha.

It must be borne in mind that the word apocrypha is really a Greek adjective in the neuter plural, denoting strictly 'things hidden.' But almost certainly the noun biblia is understood, so that the real implication of the word is 'apocryphal books' or 'writings.' In this article apocrypha will be employed in the sense of this last, and apocryphal as the equivalent of the Greek apokruphos.

1. Early Christian Usage:

'Apocalyptic' literature.

The word apocrypha was first used technically by early Christian writers for the Jewish and Christian writings usually classed under 'Apocalyptic' (see APOCALYPTIC LITERATURE). In this sense it takes the place of the classical Greek word esoterika and bears the same general meaning, namely, writings intended for an inner circle and cap. able of being understood by no others. These writings give intimations regarding the future, the ultimate triumph of the kingdom of God, etc., beyond, it was thought, human discovery and also beyond the intelligence of the uninitiated. In this sense Gregory of Nyssa (died 395; De Ordin., II, 44) and Epiphanius (died 403; Haeres, 51 3) speak of the Apocalypse of John as 'apocryphal.'

2. The Eastern Church:

Christianity itself has nothing corresponding to the idea of a doctrine for the initiated or a literature for a select few. The gospel was preached in its first days to the poor and ignorant, and the reading and studying of the sacred Scriptures have been urged by the churches (with some exceptions) upon the public at large.

(1) 'Esoteric' Literature (Clement of Alexandria, etc.).

The rise of this conception in the eastern church is easily understood. When devotees of Greek philosophy accepted the Christian faith it was natural for them to look at the new religion through the medium of the old philosophy. Many of them read into the canonical writings mystic meanings, and embodied those meanings in special books, these last becoming esoteric literature in themselves: and as in the case of apocalyptic writings, this esoteric literature was more revered than the Bible itself. In a similar way there grew up among the Jews side by side with the written law an oral law containing the teaching of the rabbis and regarded as more sacred and authoritative than the writings they profess to expound. One may find some analogy in the fact that among many Christians the official literature of the denomination to which they belong has more commanding force than the Bible itself. This movement among Greek Christians was greatly aided by Gnostic sects and the esoteric literature to which they gave rise. These Gnostics had been themselves influenced deeply by Babylonian and Persian mysticism and the corresponding literature. Clement of Alexandria (died 220) distinctly mentions esoteric books belonging to the Zoroastrian (Mazdean) religion.

Oriental and especially Greek Christianity tended to give to philosophy the place which the New Testament and western Christianity assign the Old Testament. The preparation for the religion of Jesus was said to be in philosophy much more than in the religion of the Old Testament. It will be remembered that Marcian (died end of 2nd century A.D.), Thomas Morgan, the Welsh 18th-century deist (died 1743) and Friedrich Schleiermacher (died 1834) taught this very same thing.

Clement of Alexandria (see above) recognized 4 (2) Esdras (to be hereafter called the Apocalypse of Ezra), the Assumption of Moses, etc., as fully canonical. In addition to this he upheld the authority and value of esoterical books, Jewish, Christian, and even heathen. But he is of most importance for our present purpose because he is probably the earliest Greek writer to use the word apocrypha as the equivalent of esoterika, for he describes the esoteric books of Zoroastrianism as apocryphal.

But the idea of esoteric religious literature existed at an earlier time among the Jews, and was borrowed from them by Christians. It is clearly taught in the Apocalyptic Esdras (2 or 4 Esd) chapter 14, where it is said that Ezra aided by five amanuenses produced under Divine inspiration 94 sacred books, the writings of Moses and the prophets having been lost when Jerusalem and the temple were destroyed. Of this large number of sacred books 24 were to be published openly, for the unworthy as well as the worthy, these 24 books representing undoubtedly the books of the Hebrew Old Testament. The remaining 70 were to be kept for the exclusive use of the 'wise among the people': i.e. they were of an esoteric character. Perhaps if the Greek original of this book had been preserved the word 'apocrypha' would have been found as an epithetic attached to the 70 books. Our English versions are made from a Latin original EZRA or the APOCALYPTIC ESDRAS. Modern scholars agree that in its present form this book arose in the reign of Domitian 81-96 A.D. So that the conception of esoteric literature existed among the Jews in the 1st century of our era, and probably still earlier.

It is significant of the original character of the religion of Israel that no one has been able to point to a Hebrew word corresponding to esoteric (see below). When among the Jews there arose a literature of oral tradition it was natural to apply to this last the Greek notion of esoteric, especially as this class of literature was more highly esteemed in many Jewish circles than the Old Testament Scriptures themselves.

(2) Change to 'Religious' Books (Origen, etc.).

The next step in the history of the word 'apocrypha' is that by which it came to denote religious books inferior in authority and worth to the Scriptures of the Old Testament and New Testament. This change of attitude toward noncanonical writings took place under the influence of two principles: (1) that no writer could be inspired who lived subsequent to the apostolic age; (2) that no writing could be recognized as canonical unless it was accepted as such by the churches in general (in Latin the principle was-quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus). Now it was felt that many if not most of the religious writings which came in the end of the 2nd century to be called 'apocryphal' in a disparaging sense had their origin among heretical sects like the Gnostics, and that they had never commanded the approval of the great bulk of the churches. Origen (died 253) held that we ought to discriminate between books called 'apocryphal,' some such having to be firmly rejected as teaching what is contrary to the Scriptures. More and more from the end of the 2nd century, the word 'apocrypha' came to stand for what is spurious and untrustworthy, and especially for writings ascribed to authors who did not write them: i.e. the so-called 'Pseudepigraphical books.'

Irenaeus (died 202) in opposition to Clement of Alexandria denies that esoteric writings have any claims to credence or even respect, and he uses the Greek word for 'apocryphal' to describe all Jewish and Christian canons. To him, as later to Jerome (died 420), 'canonical' and 'apocryphal' were antithetic terms. Tertullian (died 230) took the same view: 'apocryphal' to him denoted non-canonical. But both Irenaeus and Tertullian meant by apocrypha in particular the apocalyptic writings. During the Nicene period, and even earlier, sacred books were divided by Christian teachers into three classes:

(1) books that could be read in church;

(2) books that could be read privately, but not in public;

(3) books that were not to be read at all. This classification is implied in the writings of Origen, Clement of Alexandria, Athanasius (died 373), and in the Muratorian Fragments (about 200 A.D.).

(3) 'Spurious' Books (Athanasius, Nicephorus, etc.).

Athanasius, however, restricted the word apocrypha to the third class, thus making the corresponding adjective synonymous with 'spurious.' Nicephorus, patriarch of Constantinople (806-15 A.D.) in his chronography (belonging essentially to 500 A.D. according to Zahn) divides sacred books thus:

(1) the canonical books of the Old Testament and New Testament;

(2) the Antilegomena of both Testaments;

(3) the Apocrypha of both Testaments.

The details of the Apocrypha of the New Testament are thus enumerated:

(1) Enoch;

(2) The 12 Patriarchs;

(3) The Prayer of Joseph;

(4) The Testament of Moses;

(5) The Assumption of Moses;

(6) Abram;

(7) Eldad and Modad;

(8) Elijah the Prophet;

(9) Zephaniah the Prophet;

(10) Zechariah, father of John;

(11) The Pseudepigrapha of Baruch, Habakkuk, Ezekiel and Daniel.

The books of the New Testament Apocrypha are thus given:

(1) The Itinerary of Paul;

(2) The Itinerary of Peter;

(3) The Itinerary of John;

(4) The Itinerary of Thomas;

(5) The Gospel according to Thomas;

(6) The Teaching of the Apostles (the Didache);

(7) and (8) The Two Epistles of Clement;

(9) Epistles of Ignatius, Polycarp and Hermas.

The above lists are repeated in the so-called Synopsis of Athanasius. The authors of these so-called apocryphal books being unknown, it was sought to gain respect for these writers by tacking onto them well-known names, so that, particularly in the western church, 'apocryphal' came to be almost synonymous with 'pseudepigraphical.' Of the Old Testament lists given above numbers 1, 2, 4, 5 are extant wholly or in part. Numbers 3, 7, 8 and 9 are lost though quoted as genuine by Origen and other eastern Fathers. They are all of them apocalypses designated apocrypha in accordance with early usage.

(4) 'List of Sixty.'

In the anonymous, 'List of Sixty,' which hails from the 7th century, we have represented probably the attitude of the eastern church. It divides sacred books into three classes:

(1) The sixty canonical books. Since the Protestant canon consists of but 57 books it will be seen that in this list books outside our canon are included.

(2) Books excluded from the 60, yet of superior authority to those mentioned as apocryphal in the next class. (3) Apocryphal books, the names of which are as follows:

(a) Adam;

(b) Enoch;

(c) Lamech;

(d) The 12 Patriarchs;

(e) The Prayer of Joseph;

(f) Eldad and Modad;

(g) The Testament of Moses;

(h) The Assumption of Moses;

(i) The Psalms of Solomon;

(j) The Apocalypse of Elijah;

(k) The Ascension of Isaiah;

(l) The Apocalypse of Zephaniah (see number 9 of the Old Testament Apocrypha books mentioned in the Chronography of Nicephorus);

(m) The Apocalypse of Zechariah;

(n) The Apocalyptic Ezra;

(o) The History of James;

(p) The Apocalypse of Peter;

(q) The Itinerary and Teaching of the Apostles;

(r) The Epistles of Barnabas;

(s) The Acts of Paul;

(t) Apocalypse of Paul;

(u) Didascalia of Clement;

(v) Didascalia of Ignatius;

(w) Didascalia of Polycarp;

(x) Gospel according to Barnabas;

(y) Gospel according to Matthew.

The greater number of these books come under the designation 'apocryphal' in the early sense of 'apocalyptic,' but by this time the word had taken on a lower meaning, namely, books not good for even private reading. Yet the fact that these books are mentioned at all show that they were more highly esteemed than heathen and than even heretical Christian writings. The eastern churches down to the present day reject the meaning of 'apocrypha' current among Protestants (see definition above), and their Bible includes the Old Testament Apocrypha, making no distinction between it and the rest of the Bible.

3. The Western Church:

(1) The Decretum Gelasii.

In the western church the word apocrypha and the corresponding adjective had a somewhat different history. In general it may be said that the western church did not adopt the triple division of sacred books prevalent in the eastern church. Yet the Decretum Gelasii (6th century in its present form) has a triple. list which is almost certainly that of the Roman synod of 382 under Damasus, bishop of Rome, 366 to 384. It is as follows:

(1) the canonical books of both Testaments;

(2) writings of the Fathers approved by the church;

(3) apocryphal books rejected by the church.

Then there is added a list of miscellaneous books condemned as heretical, including even the works of Clement of Alexandria, Tertullian, and Eusebius, these works being all branded as 'apocryphal.' On the other hand Gregory of Nyssa and Epiphanius, both writing in the 4th century, use the word 'apocrypha' in the old sense of apocalyptic, i.e. esoteric.

(2) 'Non-Canonical' Books.

Jerome (died 420) in the Prologus Galeatus (so called because it was a defense and so resembled a helmeted warrior) or preface to his Latin version of the Bible uses the word 'Apocrypha' in the sense of non-canonical books. His words are: Quidquid extra hos (i.e. the 22 canonical books) inter Apocrypha ponendum: 'Anything outside of these must be placed within the Apocrypha' (when among the Fathers and rabbis the Old Testament is made to contain 22 (not 24) books, Ruth and Lamentations are joined respectively to Judges and Jeremiah). He was followed in this by Rufinus (died circa 410), in turns Jerome's friend and adversary, as he had been anticipated by Irenaeus. The western church as a whole departed from Jerome's theory by including the antilegomena of both Testaments among the canonical writings: but the general custom of western Christians about this time was to make apocryphal mean non-canonical. Yet Augustine (died 430; De Civitale Dei, XV, 23) explained the 'apocrypha' as denoting obscurity of origin or authorship, and this sense of the word became the prevailing one in the West.

4. The Reformers:

Separation from Canonical Books.

But it is to the Reformers that we are indebted for the habit of using Apocrypha for a collection of books appended to the Old Testament and generally up to 1827 appended to every printed English Bible. Bodenstein of Carlstadt, usually called Carlstadt (died 1541), an early Reformer, though Luther's bitter personal opponent, was the first modern scholar to define 'Apocrypha' quite clearly as writings excluded from the canon, whether or not the true authors of the books are known, in this, going back to Jerome's position. The adjective 'apocryphal' came to have among Protestants more and more a disparaging sense. Protestantism was in its very essence the religion of a book, and Protestants would be sure to see to it that the sacred volume on which they based their religion, including the reforms they introduced, contained no book but those which in their opinion had the strongest claims to be regarded as authoritative.

In the eastern and western churches under the influence of the Greek (Septuagint) and Latin (Vulgate) versions the books of the Apocrypha formed an integral part of the canon and were scattered throughout the Old Testament, they being placed generally near books with which they have affinity. Even Protestant Bibles up to 1827 included the Apocrypha, but as one collection of distinct writings at the end of the Old Testament. It will be seen from what has been said that notwithstanding the favorable attitude toward it of the eastern and western churches, from the earliest times, our Apocrypha was regarded with more or less suspicion, and the suspicion would be strengthened by the general antagonism toward it. In the Middle Ages, under the influence of Reuchlin (died 1532)-great scholar and Reformer-Hebrew came to be studied and the Old Testament read in its original language. The fact that the Apocrypha is absent from the Hebrew canon must have had some influence on the minds of the Reformers.

Moreover in the Apocrypha there are parts inconsistent with Protestant principles, as for example the doctrines of prayers for the dead, the intercession of the saints, etc. The Jews in the early Christian centuries had really two Bibles: (1) There was the Hebrew Bible which does not include the Apocrypha, and which circulated in Palestine and Babylon; (2) there was the Greek version (Septuagint) used by Greek-speaking Jews everywhere. Until in quite early times, instigated by the use made of it by Christians against themselves, the Jews condemned this version and made the Hebrew canon their Bible, thus rejecting the books of the Apocrypha from their list of canonical writings, and departing from the custom of Christian churches which continued with isolated remonstrances to make the Greek Old Testament canon, with which the Vulgate agrees almost completely, their standard. It is known that the Reformers were careful students of the Bible, and that in Old Testament matters they were the pupils of Jewish scholars-there were no other competent teachers of Hebrew. It might therefore have been expected that the Old Testament canon of the Reformers would agree in extent with that of the Jews and not with that of the Greek and Latin Christians. Notwithstanding the doubt which Ryle (Canon of the Old Testament, 156) casts on the matter, all the evidence goes to show that the Septuagint and therefore the other great Greek versions included the Apocrypha from the first onward.

But how comes it to be that the Greek Old Testament is more extensive than the Hebrew Old Testament? Up to the final destruction of Jerusalem in 71 A.D. the temple with its priesthood and ritual was the center of the religious thought and life of the nation. But with the destruction of the sanctuary and the disbanding of its officials it was needful to find some fresh binding and directing agency and this was found in the collection of sacred writings known by us as the Old Testament. By a national synod held at Jamnia, near Jaffa, in 90 A.D., the Old Testament canon was practically though not finally closed, and from that date one may say that the limits of the Old Testament were once and for all fixed, no writings being included except those written in Hebrew, the latest of these being as old as 100 B.C. Now the Jews of the Dispersion spoke and wrote Greek, and they continued to think and write long after their fellow-countrymen of the homeland had ceased to produce any fresh original literature. What they did produce was explanatory of what had been written and practical.

The Greek Bible-the Septuagint-is that of the Jews in Egypt and of those found in other Greek-speaking countries. John Wycliffe (died 1384) puts the Apocrypha together at the end of the Old Testament and the same course was taken by Luther (1546) in his great German and by Miles Coverdale (died 1568) in his English translation.

5. Hebrew Words for 'Apocrypha':

Is it quite certain that there is no Hebrew word or expression corresponding exactly to the word 'apocrypha' as first used by Christian writers, i.e. in the sense 'esoteric'? One may answer this by a decisive negative as regards the Old Testament and the Talmud. But in the Middle Ages qabbalah (literally, 'tradition') came to have 'a closely allied meaning (compare our 'kabbalistic').

(1) Do such exist?

Is there in Hebrew a word or expression denoting 'non-canonical,' i.e. having the secondary sense acquired by 'apocrypha'? This question does not allow of so decided an answer, and as matter of fact it has been answered in different ways.

(2) Views of Zahn, Schurer, Porter, etc. (ganaz, genuzim).

Zahn (Gesch. des neutest. Kanons, I, i, 123); Schurer (RE3, I, 623); Porter (HDB, I) and others maintain that the Greek word 'Apocrypha (Biblia)' is a translation of the Hebrew Cepharim genuzim, literally, 'books stored away.' If this view is the correct one it follows that the distinction of canonical and non-canonical books originated among the Jews, and that the Fathers in using the word apocrypha in this sense were simply copying the Jews substituting Greek words for the Hebrew equivalent. But there are decisive reasons for rejecting this view.

(3) Reasons for Rejection.

(a) The verb ganaz of which the passive part. occurs in the above phrase means 'to store away,' 'to remove from view'-of things in themselves sacred or precious. It never means to exclude as from the canon.

(b) When employed in reference to sacred books it is only of those recognized as canonical. Thus after copies of the Pentateuch or of other parts of the Hebrew Bible had, by age and use, become unfit to be read in the home or in the synagogue they were 'buried' in the ground as being too sacred to be burnt or cut up; and the verb denoting this burying is ganaz. But those buried books are without exception canonical.

(c) The Hebrew phrase in question does not once occur in either the Babylonian or the Jerusalem Talmud, but only in rabbinical writings of a much later date. The Greek apocrypha cannot therefore be a rendering of the Hebrew expression. The Hebrew for books definitely excluded from the canon is Cepharim chitsonim = 'outside' or 'extraneous books.' The Mishna (the text of the Gemara, both making up what we call the Talmud) or oral law with its additions came to be divided analogously into

(1) The Mishna proper;

(2) the external (chitsonah) Mishna: in Aramaic called Baraiytha'.

6. Summary:

What has been said may be summarized:

(1) Among the Protestant churches the word 'Apocrypha' is used for the books included in the Septuagint and Vulgate, but absent from the Hebrew Bible. This restricted sense of the word cannot be traced farther back than the beginning of the Reformation.

(2) In classical and Hellenistic Greek the adjective apokruphos denotes 'hidden' of visible objects, or obscure, hard to understand (of certain kinds of knowledge).

(3) In early patristic Greek this adjective came into use as a synonym of the classical Greek esoterikos.

(4) In later patristic Greek (Irenaeus, etc.) and in Latin works beginning with Jerome, Greek apokruphos meant non-canonical, implying inferiority in subject-matter to the books in the canon.

(4) By the Protestant Reformers the term 'apocrypha' ('apocryphal' 'books' being understood) came to stand for what is now called the 'Old Testament Apocrypha.' But this usage is confined to Protestants, since in the eastern church and in the Roman branch of the western church the Old Testament Apocrypha is as much an integral part of the canon as Genesis or Kings or Psalms or Isaiah.

(5) There are no equivalents in Hebrew for apokruphos in the sense of either 'esoteric' or in that of 'non-canonical.'

IV. Contents of the Apocrypha.

1. List of Books:

The following is a list of the books in the Apocrypha in the order in which they occur in the English versions (the King James Version and the Revised Version (British and American)):

(1) 1 Esdras;

(2) 2 Esdras (to be hereafter called 'The Apocalyptic Esdras');

(3) Tobit;

(4) Judith;

(5) The Rest of Esther;

(6) The Wisdom of Solomon;

(7) Ecclesiasticus (to be hereafter called 'Sirach');

(8) Baruch, with the Epistle of Jeremiah;

(9) The So of the Three Holy Children; (10) The History of Susanna;

(11) Bel and the Dragon;

(12) The Prayer of Manasses;

(13) 1 Maccabees;

(14) 2 Maccabees.

No. 5 in the above, 'Addition to Esther;' as it may be called, consists of the majority (107 out of 270 verses) of the Book of Esther since it occurs in the best manuscripts of the Septuagint and in the Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) over the text in the Hebrew Bible. These additions are in the Septuagint scattered throughout the book and are intelligible in the context thus given them, but not when brought together as they are in the collected Apocrypha of our English versions and as they are to some extent in Jerome's Latin version and the Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 A.D.) (see The Century Bible, Ezra, Nehemiah and Esther, 294f). Numbers 9-11 in the above enumeration are additions made in the Greek Septuagint and Vulgate versions of Daniel to the book as found in the Massoretic Text.

STRANGER AND SOJOURNER (IN THE APOCRYPHA AND THE NEW TESTAMENT)

The technical meaning attaching to the Hebrew terms is not present in the Greek words translated 'stranger' and 'sojourner,' and the distinctions made by English Versions of the Bible are partly only to give uniformity in the translation. For 'stranger' the usual Greek word is xenos, meaning primarily 'guest' and so appearing in the combination 'hatred toward guests' in The Wisdom of Solomon 19:13 (misoxenia). Xenos is the most common word for 'stranger' in the New Testament (Matthew 25:35, etc.), but it seems not to be used by itself with this force in the Apocrypha. Almost equally common in the New Testament is allotrios, 'belonging to another' (Matthew 17:25, 26John 10:5 (bis)), and this is the usual word in the Apocrypha (Sirach 8:18; 1 Maccabees 1:38, etc.), but for some inexplicable reason the Revised Version (British and American) occasionally translates by 'alien' (contrast, e.g. 1 Maccabees 1:38; 2:7). Compare the corresponding verb apallotrioo (Ephesians 2:12; Ephesians 4:18Colossians 1:21). With the definite meaning of 'foreigner' are allogenes, 'of another nation,' the Revised Version (British and American) 'stranger' (1 Esdras 8:83; 1 Maccabees 3:45 (the King James Version 'alien'); Luke 17:18 (the Revised Version margin 'alien')), and allophulos, 'of another tribe,' the Revised Version (British and American) 'stranger' (Baruch 6:5; 1 Maccabees 4:12, etc.) or 'of another nation' (Acts 10:28). For 'to sojourn' the commonest form is paroikeo, 'to dwell beside,' the Revised Version (British and American) always 'to sojourn' (Judith 5:7; Sirach 41:19; Luke 24:18 (the King James Version 'to be a stranger'); Hebrews 11:9). The corresponding noun for 'sojourner' is paroikos (Sirach 29:26 (the King James Version 'stranger'); Acts 7:6, 26Ephesians 2:191 Peter 2:11), with paroikia, 'sojourning' (The Wisdom of Solomon 19:10; Sirach 16:8; Acts 13:17 (the King James Version 'dwelling as strangers'); 1 Peter 1:17). In addition, epidemeo, 'to be among people,' is translated 'to sojourn' in Acts 2:10; Acts 17:21, and its compound parepidemos, as 'sojourner' in 1 Peter 1:1 (in Hebrews 11:131 Peter 2:11, 'pilgrim').

Burton Scott Easton

... [3794 () is also used for a in antiquity (). 'The word is not common in

Classical Greek, but occurs frequently in the Apocrypha. ...

//strongsnumbers.com/greek2/3794.htm - 7k

Apocrypha of the New Testament

Apocrypha of the New Testament. <. ... Alexander Walker, Esq. (Translator)

Table of Contents. Title Page. Apocrypha of the New Testament. ...

//christianbookshelf.org/unknown/apocrypha of the new testament/

Introductory Notice to Apocrypha of the New Testament.

Apocrypha of the New Testament. <. ...Apocrypha of the New Testament.

Translated by Alexander Walker, Esq., One of Her Majesty's ...

/.../unknown/apocrypha of the new testament/introductory notice to apocrypha of.htm

Apocrypha of the New Testament

Apocrypha of the New Testament. <. ...

//christianbookshelf.org/unknown/apocrypha of the new testament/title page.htm

The Old Faith Preparing for the New - Development of Hellenist ...

... THE OLD FAITH PREPARING FOR THE NEW - DEVELOPMENT OF HELLENIST THEOLOGY: THE APOCRYPHA,

ARISTEAS, ARISTOBULUS, AND THE PSEUDEPIGRAPHIC WRITINGS. ...

/.../edersheim/the life and times of jesus the messiah/chapter iii the old faith.htm

The Arabic Gospel of the Infancy of the Saviour (Nt Apocrypha)

... The Arabic Gospel of the Infancy of the Saviour (NT Apocrypha). Introduction In

the name of the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit, one God. ...

/.../the arabic gospel of the infancy of the saviour/the arabic gospel of the.htm

Of Passages from the Holy Scriptures, and from the Apocrypha...

... OF PASSAGES FROM THE HOLY SCRIPTURES, AND FROM THE APOCRYPHA, WHICH ARE QUOTED,

OR INCIDENTALLY ILLUSTRATED, IN THE INSTITUTES. INDEX TO. ...

/.../calvin/the institutes of the christian religion/of passages from the holy.htm

By the Same Author.

... The Use of the Apocrypha in the Christian Church. ... Price 3s. ADBOOKMAN.'A lucid

setting forth of the Ancient and Modern Use of the Apocrypha.'. ...

/.../daubney/the three additions to daniel a study/by the same author.htm

Translator's Introductory Notice.

Apocrypha of the New Testament. <. ...Apocrypha of the New Testament.

Translated by Alexander Walker, Esq., One of Her Majesty's ...

/.../unknown/apocrypha of the new testament/translators introductory notice.htm

But it Should be Known that There are Also Other Books which Our ...

... confirmation of doctrine. The other writings they have named 'Apocrypha.'

These they would not have read in the Churches. 38. But it ...

/.../38 but it should be.htm

Apocryphal Apocalypses.

Apocrypha of the New Testament. <. ...Apocrypha of the New Testament.

Translated by Alexander Walker, Esq., One of Her Majesty's ...

/.../unknown/apocrypha of the new testament/part iii apocryphal apocalypses.htm

... The Old Testament Apocrypha consists of fourteen books, the chief of which are the

Books of the Maccabees (qv), the Books of Esdras, the Book of Wisdom, the ...

/a/apocrypha.htm - 48k

Revised

... 4. Apocrypha: No American Standard Revised Version Apocrypha was attempted, a

particularly unfortunate fact, as the necessity for the study of the Apocrypha...

/r/revised.htm - 12k

American

... 4. Apocrypha: No American Standard Revised Version Apocrypha was attempted, a

particularly unfortunate fact, as the necessity for the study of the Apocrypha...

/a/american.htm - 13k

Armenian

... I. ANCIENT ARMENIAN 1. Circumstances under Which Made 2. The Translators Apocrypha

Omitted 3. Revision 4. Results of Circulation 5. Printed Editions II. ...

/a/armenian.htm - 18k

Manasses (1 Occurrence)

... the Vulgate (Jerome's Latin Bible, 390-405 AD) is 'A Prayer of Manasses, King of

Judah, when He Was Held Captive in Babylon.' In Baxter's Apocrypha, Greek and ...

/m/manasses.htm - 19k

Jeremy (2 Occurrences)

... In Fritzsche, Lib. Apocrypha VT Graece, Epistle Jeremiah stands between Baruch and

Tobit. ... LITERATURE. See under APOCRYPHA for commentary and various editions. ...

/j/jeremy.htm - 12k

Stranger (152 Occurrences)

... 7. (vt) To estrange; to alienate. Int. Standard Bible Encyclopedia. STRANGER

AND SOJOURNER (IN THE APOCRYPHA AND THE NEW TESTAMENT). ...

/s/stranger.htm - 57k

Sojourner (81 Occurrences)

... Noah Webster's Dictionary (n.) One who sojourns. Int. Standard Bible Encyclopedia.

STRANGER AND SOJOURNER (IN THE APOCRYPHA AND THE NEW TESTAMENT). ...

/s/sojourner.htm - 48k

Malefactor (2 Occurrences)

... John 5:1-3). William Evans. STRANGER AND SOJOURNER (IN THE APOCRYPHA AND

THE NEW TESTAMENT). The technical meaning attaching to the ...

/m/malefactor.htm - 49k

Rest (831 Occurrences)

... unintelligible. In English, Welsh and other Protestant versions of the

Scriptures the whole of the additions appear in the Apocrypha. ...

/r/rest.htm - 47k

How do we know that the Bible is the Word of God, and not the Apocrypha, the Qur'an, the Book of Mormon, etc.? | GotQuestions.org

Apocrypha and Pseudepigrapha ' Article Index | GotQuestions.org

Apocrypha: Dictionary and Thesaurus | Clyx.com

Bible Concordance • Bible Dictionary • Bible Encyclopedia • Topical Bible • Bible Thesuarus

| Bible Research >English Versions >20th Century >NRSV > Preface |

This preface is addressed to you by the Committee of translators, who wish to explain, as briefly as possible, the origin and character of our work. The publication of our revision is yet another step in the long, continual process of making the Bible available in the form of the English language that is most widely current in our day. To summarize in a single sentence: the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible is an authorized revision of the Revised Standard Version, published in 1952, which was a revision of the American Standard Version, published in 1901, which, in turn, embodied earlier revisions of the King James Version, published in 1611.

In the course of time, the King James Version came to be regarded as 'the Authorized Version.' With good reason it has been termed 'the noblest monument of English prose,' and it has entered, as no other book has, into the making of the personal character and the public institutions of the English-speaking peoples. We owe to it an incalculable debt.

Yet the King James Version has serious defects. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the development of biblical studies and the discovery of many biblical manuscripts more ancient than those on which the King James Version was based made it apparent that these defects were so many as to call for revision. The task was begun, by authority of the Church of England, in 1870. The (British) Revised Version of the Bible was published in 1881-1885; and the American Standard Version, its variant embodying the preferences of the American scholars associated with the work, was published, as was mentioned above, in 1901. In 1928 the copyright of the latter was acquired by the International Council of Religious Education and thus passed into the ownership of the churches of the United States and Canada that were associated in this Council through their boards of education and publication.

The Council appointed a committee of scholars to have charge of the text of the American Standard Version and to undertake inquiry concerning the need for further revision. After studying the questions whether or not revision should be undertaken, and if so, what its nature and extent should be, in 1937 the Council authorized a revision. The scholars who served as members of the Committee worked in two sections, one dealing with the Old Testament and one with the New Testament. In 1946 the Revised Standard Version of the New Testament was published. The publication of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible, containing the Old and New Testaments, took place on September 30, 1952. A translation of the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament followed in 1957. In 1977 this collection was issued in an expanded edition, containing three additional texts received by Eastern Orthodox communions (3 and 4 Maccabees and Psalm 151). Thereafter the Revised Standard Version gained the distinction of being officially authorized for use by all major Christian churches: Protestant, Anglican, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox.

The Revised Standard Version Bible Committee is a continuing body, comprising about thirty members, both men and women. Ecumenical in representation, it includes scholars affiliated with various Protestant denominations, as well as several Roman Catholic members, an Eastern Orthodox member, and a Jewish member who serves in the Old Testament section. For a period of time the Committee included several members from Canada and from England.

Because no translation of the Bible is perfect or is acceptable to all groups of readers, and because discoveries of older manuscripts and further investigation of linguistic features of the text continue to become available, renderings of the Bible have proliferated. During the years following the publication of the Revised Standard Version, twenty-six other English translations and revisions of the Bible were produced by committees and by individual scholars—not to mention twenty-five other translations and revisions of the New Testament alone. One of the latter was the second edition of the RSV New Testament, issued in 1971, twenty-five years after its initial publication.

Following the publication of the RSV Old Testament in 1952, significant advances were made in the discovery and interpretation of documents in Semitic languages related to Hebrew. In addition to the information that had become available in the late 1940s from the Dead Sea texts of Isaiah and Habakkuk, subsequent acquisitions from the same area brought to light many other early copies of all the books of the Hebrew Scriptures (except Esther), though most of these copies are fragmentary. During the same period early Greek manuscript copies of books of the New Testament also became available.

In order to take these discoveries into account, along with recent studies of documents in Semitic languages related to Hebrew, in 1974 the Policies Committee of the Revised Standard Version, which is a standing committee of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., authorized the preparation of a revision of the entire RSV Bible.

For the Old Testament the Committee has made use of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1977; ed. sec. emendata, 1983). This is an edition of the Hebrew and Aramaic text as current early in the Christian era and fixed by Jewish scholars (the 'Masoretes') of the sixth to the ninth centuries. The vowel signs, which were added by the Masoretes, are accepted in the main, but where a more probable and convincing reading can be obtained by assuming different vowels, this has been done. No notes are given in such cases, because the vowel points are less ancient and reliable than the consonants. When an alternative reading given by the Masoretes is translated in a footnote, this is identified by the words 'Another reading is.'

Departures from the consonantal text of the best manuscripts have been made only where it seems clear that errors in copying had been made before the text was standardized. Most of the corrections adopted are based on the ancient versions (translations into Greek, Aramaic, Syriac, and Latin), which were made prior to the time of the work of the Masoretes and which therefore may reflect earlier forms of the Hebrew text. In such instances a footnote specifies the version or versions from which the correction has been derived and also gives a translation of the Masoretic Text. Where it was deemed appropriate to do so, information is supplied in footnotes from subsidiary Jewish traditions concerning other textual readings (the Tiqqune Sopherim, 'emendations of the scribes'). These are identified in the footnotes as 'Ancient Heb tradition.'

Occasionally it is evident that the text has suffered in transmission and that none of the versions provides a satisfactory restoration. Here we can only follow the best judgment of competent scholars as to the most probable reconstruction of the original text. Such reconstructions are indicated in footnotes by the abbreviation Cn ('Correction'), and a translation of the Masoretic Text is added.

For the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament the Committee has made use of a number of texts. For most of these books the basic Greek text from which the present translation was made is the edition of the Septuagint prepared by Alfred Rahlfs and published by the Württemberg Bible Society (Stuttgart, 1935). For several of the books the more recently published individual volumes of the Göttingen Septuagint project were utilized. For the book of Tobit it was decided to follow the form of the Greek text found in codex Sinaiticus (supported as it is by evidence from Qumran); where this text is defective, it was supplemented and corrected by other Greek manuscripts. For the three Additions to Daniel (namely, Susanna, the Prayer of Azariah and the Song of the Three Jews, and Bel and the Dragon) the Committee continued to use the Greek version attributed to Theodotion (the so-called 'Theodotion-Daniel'). In translating Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), while constant reference was made to the Hebrew fragments of a large portion of this book (those discovered at Qumran and Masada as well as those recovered from the Cairo Geniza), the Committee generally followed the Greek text (including verse numbers) published by Joseph Ziegler in the Göttingen Septuagint (1965). But in many places the Committee has translated the Hebrew text when this provides a reading that is clearly superior to the Greek; the Syriac and Latin versions were also consulted throughout and occasionally adopted. The basic text adopted in rendering 2 Esdras is the Latin version given in Biblia Sacra, edited by Robert Weber (Stuttgart, 1971). This was supplemented by consulting the Latin text as edited by R. L. Bensly (1895) and by Bruno Violet (1910), as well as by taking into account the several Oriental versions of 2 Esdras, namely, the Syriac, Ethiopic, Arabic (two forms, referred to as Arabic 1 and Arabic 2), Armenian, and Georgian versions. Finally, since the Additions to the Book of Esther are disjointed and quite unintelligible as they stand in most editions of the Apocrypha, we have provided them with their original context by translating the whole of the Greek version of Esther from Robert Hanhart's Göttingen edition (1983).

For the New Testament the Committee has based its work on the most recent edition of The Greek New Testament, prepared by an interconfessional and international committee and published by the United Bible Societies (1966; 3rd ed. corrected, 1983; information concerning changes to be introduced into the critical apparatus of the forthcoming 4th edition was available to the Committee). As in that edition, double brackets are used to enclose a few passages that are generally regarded to be later additions to the text, but which we have retained because of their evident antiquity and their importance in the textual tradition. Only in very rare instances have we replaced the text or the punctuation of the Bible Societies' edition by an alternative that seemed to us to be superior. Here and there in the footnotes the phrase, 'Other ancient authorities read,' identifies alternative readings preserved by Greek manuscripts and early versions. In both Testaments, alternative renderings of the text are indicated by the word 'Or.'

As for the style of English adopted for the present revision, among the mandates given to the Committee in 1980 by the Division of Education and Ministry of the National Council of Churches of Christ (which now holds the copyright of the RSV Bible) was the directive to continue in the tradition of the King James Bible, but to introduce such changes as are warranted on the basis of accuracy, clarity, euphony, and current English usage. Within the constraints set by the original texts and by the mandates of the Division, the Committee has followed the maxim, 'As literal as possible, as free as necessary.' As a consequence, the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV) remains essentially a literal translation. Paraphrastic renderings have been adopted only sparingly, and then chiefly to compensate for a deficiency in the English language—the lack of a common gender third person singular pronoun.

During the almost half a century since the publication of the RSV, many in the churches have become sensitive to the danger of linguistic sexism arising from the inherent bias of the English language towards the masculine gender, a bias that in the case of the Bible has often restricted or obscured the meaning of the original text. The mandates from the Division specified that, in references to men and women, masculine-oriented language should be eliminated as far as this can be done without altering passages that reflect the historical situation of ancient patriarchal culture. As can be appreciated, more than once the Committee found that the several mandates stood in tension and even in conflict. The various concerns had to be balanced case by case in order to provide a faithful and acceptable rendering without using contrived English. Only very occasionally has the pronoun 'he' or 'him' been retained in passages where the reference may have been to a woman as well as to a man; for example, in several legal texts in Leviticus and Deuteronomy. In such instances of formal, legal language, the options of either putting the passage in the plural or of introducing additional nouns to avoid masculine pronouns in English seemed to the Committee to obscure the historic structure and literary character of the original. In the vast majority of cases, however, inclusiveness has been attained by simple rephrasing or by introducing plural forms when this does not distort the meaning of the passage. Of course, in narrative and in parable no attempt was made to generalize the sex of individual persons.

Another aspect of style will be detected by readers who compare the more stately English rendering of the Old Testament with the less formal rendering adopted for the New Testament. For example, the traditional distinction between shall and will in English has been retained in the Old Testament as appropriate in rendering a document that embodies what may be termed the classic form of Hebrew, while in the New Testament the abandonment of such distinctions in the usage of the future tense in English reflects the more colloquial nature of the koine Greek used by most New Testament authors except when they are quoting the Old Testament.

Careful readers will notice that here and there in the Old Testament the word Lord (or in certain cases God) is printed in capital letters. This represents the traditional manner in English versions of rendering the Divine Name, the 'Tetragrammaton' (see the notes on Exodus 3.14, 15), following the precedent of the ancient Greek and Latin translators and the long established practice in the reading of the Hebrew Scriptures in the synagogue. While it is almost if not quite certain that the Name was originally pronounced 'Yahweh,' this pronunciation was not indicated when the Masoretes added vowel sounds to the consonantal Hebrew text. To the four consonants YHWH of the Name, which had come to be regarded as too sacred to be pronounced, they attached vowel signs indicating that in its place should be read the Hebrew word Adonai meaning 'Lord' (or Elohim meaning 'God'). Ancient Greek translators employed the word Kyrios ('Lord') for the Name. The Vulgate likewise used the Latin word Dominus ('Lord'). The form 'Jehovah' is of late medieval origin; it is a combination of the consonants of the Divine Name and the vowels attached to it by the Masoretes but belonging to an entirely different word. Although the American Standard Version (1901) had used 'Jehovah' to render the Tetragrammaton (the sound of Y being represented by J and the sound of W by V, as in Latin), for two reasons the Committees that produced the RSV and the NRSV returned to the more familiar usage of the King James Version. (1) The word 'Jehovah' does not accurately represent any form of the Name ever used in Hebrew. (2) The use of any proper name for the one and only God, as though there were other gods from whom the true God had to be distinguished, began to be discontinued in Judaism before the Christian era and is inappropriate for the universal faith of the Christian Church.

It will be seen that in the Psalms and in other prayers addressed to God the archaic second person singular pronouns (thee, thou, thine) and verb forms (art, hast, hadst) are no longer used. Although some readers may regret this change, it should be pointed out that in the original languages neither the Old Testament nor the New makes any linguistic distinction between addressing a human being and addressing the Deity. Furthermore, in the tradition of the King James Version one will not expect to find the use of capital letters for pronouns that refer to the Deity—such capitalization is an unnecessary innovation that has only recently been introduced into a few English translations of the Bible. Finally, we have left to the discretion of the licensed publishers such matters as section headings, cross-references, and clues to the pronunciation of proper names.

This new version seeks to preserve all that is best in the English Bible as it has been known and used through the years. It is intended for use in public reading and congregational worship, as well as in private study, instruction, and meditation. We have resisted the temptation to introduce terms and phrases that merely reflect current moods, and have tried to put the message of the Scriptures in simple, enduring words and expressions that are worthy to stand in the great tradition of the King James Bible and its predecessors.

In traditional Judaism and Christianity, the Bible has been more than a historical document to be preserved or a classic of literature to be cherished and admired; it is recognized as the unique record of God's dealings with people over the ages. The Old Testament sets forth the call of a special people to enter into covenant relation with the God of justice and steadfast love and to bring God's law to the nations. The New Testament records the life and work of Jesus Christ, the one in whom 'the Word became flesh,' as well as describes the rise and spread of the early Christian Church. The Bible carries its full message, not to those who regard it simply as a noble literary heritage of the past or who wish to use it to enhance political purposes and advance otherwise desirable goals, but to all persons and communities who read it so that they may discern and understand what God is saying to them. That message must not be disguised in phrases that are no longer clear, or hidden under words that have changed or lost their meaning; it must be presented in language that is direct and plain and meaningful to people today. It is the hope and prayer of the translators that this version of the Bible may continue to hold a large place in congregational life and to speak to all readers, young and old alike, helping them to understand and believe and respond to its message.

For the Committee,

Bruce M. Metzger

Very Rare Medieval Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures Verses

Very Rare Medieval Apocrypha Iiirejected Scriptures King James Version

| Bible Research >English Versions >20th Century >NRSV > Preface |